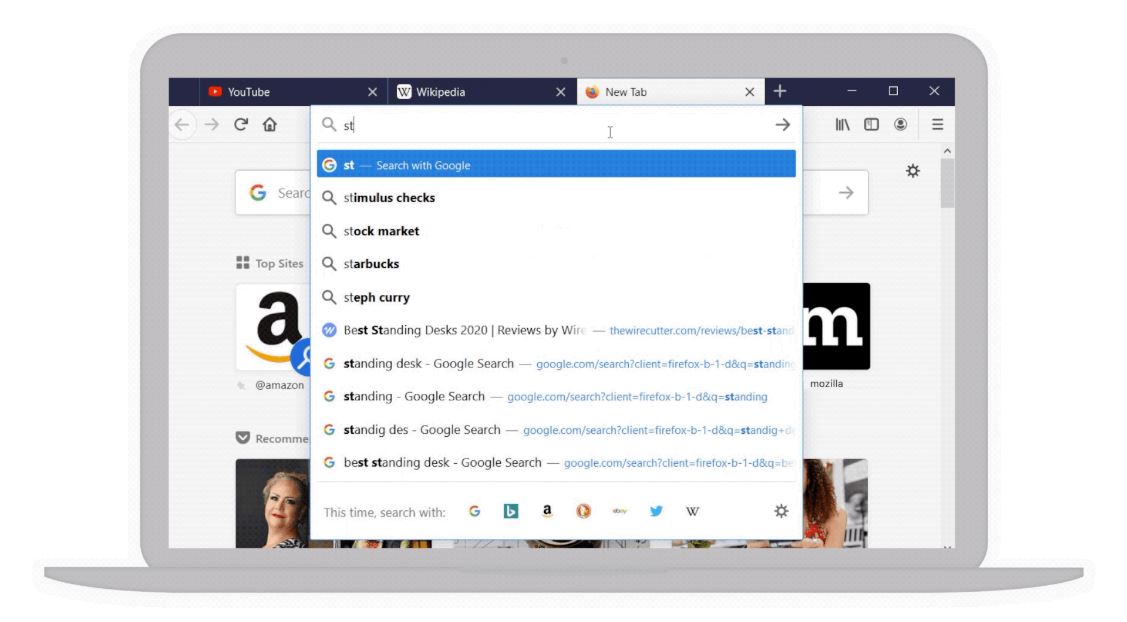

“Password” was then pasted into the address bar, and deleted in like manner. At the 9th minute of testing, “brave” (an example of a potential search term) was typed into the address bar, and subsequently deleted character by character. Once the New Tab Page had been reached, the browser was left alone for 4 minutes. Any offer to enable the collection of data, personalization, syncing, etc., was denied and/or dismissed. After this time only necessary interactions were made to arrive at a usable New Tab Page. Telerik Fiddler (v4.45441) was then used to capture network requests for 10 minutes per browser.Īside from launching the application, no user-interactions took place for the first 5 minutes. All browsers were confirmed to be up to date.

#Firefox now sends address bar keystrokes windows 10#

Each of these readings were conducted on an updated Windows 10 (Version 20H2, Build 19042.804) desktop computer, with an authenticated Microsoft account.Įach analysis was preceded by the clearing of any pre-existing profile data from the device by removing browser-specific files from Windows’ %appdata% and %localappdata% directories. This effort compared the first-run experiences of five popular browsers: Brave, Chrome, Firefox, Edge, and Opera. Similar efforts have been conducted by others, such as the 2020 work of Douglas Leith, which will be referenced throughout this review. It’s important to us that we keep a close eye on Brave in particular. In the past we at Brave have taken a look at desktop and iOS browsers, to see what they do in the first moments of being launched with a fresh user profile.

Often, a cursory examination will tell you a great deal about how the browser thinks about, and handles, user privacy and security.

You can learn quite a bit about a browser from observing the requests it makes in its first moments with a new user profile. When a Web browser first launches, it typically goes through an initial setup phase where various resources are requested, downloaded, configured, and more.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)